The following post is authored by Catherine Chen as part of the Sizing Ocean Giants project. This post originally occurred on the Story of Size.

The following post is authored by Catherine Chen as part of the Sizing Ocean Giants project. This post originally occurred on the Story of Size.

Sixty million times. That’s really big, but just how big?

- 60 million kilometers is almost half the distance from the Earth to the sun.

- 60 million times bigger is a baby born at 7.5 pounds growing to 450 million pounds

- … or $60m is a measly 0. 00035% of America’s debt. Hah. Anyway.

So 60 million is big enough that it’s hard to conceptualize (and as it turns out, provide interesting examples for) and doesn’t seem all that relevant. Except…

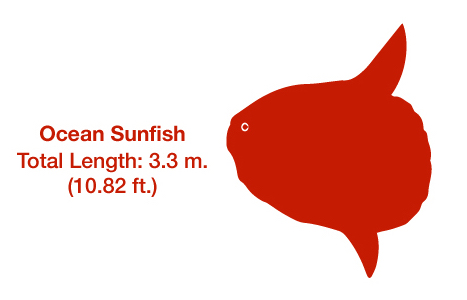

Enter the ocean sunfish (Mola mola, Latin for millstone), possessor of what must be one of the derpiest faces in the animal kingdom. Heck, it’s not even only the face. Just look at the dang thing:

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It’s been called the Eeyore of the ocean, which I think is a bit of an insult to Eeyore, because at least he’s got a proper tail. But turns out that for all its silliness, the mola manages to grow a whopping 60 million times its original size during the course of its lifetime. That’s one freaking big Eeyore.

Mola actually start as small bizarre-looking tiny 2.5mm long larvae, although it’s been estimated that the eggs are approximately 1/20th of an inch, or 1.25 millimeters. The little Molas have a long way to grow.

Creds: australianmuseum.net.au

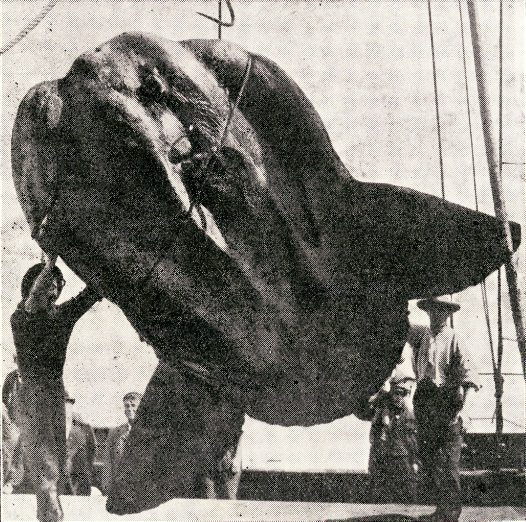

That cute little guy can become this:

Whoa.

And although the lifespan of a wild Mola is unknown, that’s still an awful lot of growing in not all that much time. In captivity, a young Mola grew a staggering 823 pounds (373kg) in a little less than three months, before its keepers rightly decided it needed to be released while they still had the ability to transport it safely to the ocean.

The biggest ocean sunfish ever found was an unfortunate fellow who hit the steamship the SS Fiona in 1908 with a “violent concussion.” (One can only imagine that the fishermen aboard the boat were rather alarmed at the giant thud that must have occurred.) After being towed to shore, the fish was measured to be 3.1 meters in length, 4.26 meters tall, and supposedly weighing 4927 pounds. Molas have consequently been graced with the well-deserved title of the world’s largest bony fish by the Guinness Book of World Records.

Their large size leads to some interesting results. For starters, how on Earth do creatures this big control their buoyancy? That is, why don’t they sink like rocks? After all, they lack the swim bladder that so often controls that job in other fish. The Mola has developed its own method (of course, because this fish isn’t special enough as is) for avoiding the fate of permanently sinking into the depths: a thick layer of gelatinous tissue surrounds the whole fish. This subcutaneous layer has been found to be as thick as 0.21 meters and to make up as much as 44% of the Mola’s body mass.

Creds: Mark Fickett, Wikimedia Commons

Their huge bulk has also led to a rather unexpected consequence: viewed from a distance, a Mola swimming along is sometimes mistaken for a shark, (why you gotta be so sneaky mola?) with their large fins and bodies. However, any matter of time spent watching that fin approach is likely to replace the vague fear you feel with amusement instead. The way that the sunfish move their bodies along is uh, distinctive, and really, their swimming just looks so wrong (especially if you’re expecting a sleek shark).

Instead, you get this:

The synchronous movement of the dorsal and anal fins manages to propel the mola along at a decent clip of 0.4-0.7 meters per second, similar to the speed of other large fishes such as salmon and marlins. Who woulda thunk? Biologists used to believe that their shape meant that molas were slow awkward swimmers, but now those darn creatures have gone and proved everyone wrong.

It’s okay, at least we’re still way better looking.

- To read the original article that first suggested the figure of 60 million, check out Gudger’s appropriately titled “From Atom to Colossus.”

- The first aquarium to keep Molas in the United States was the Monterey Bay Aquarium, where the mola that grew at an astronomical rate was kept. Read the original story in A Fascination for Fish: Adventures of an Underwater Pioneer by David Powell (2001).

- Interested in the speed of the sunfish and its gelatinous layer?

- For a great overall review of what we currently know about the Mola mola, refer to Pope et. Al 2010.

- For more Mola entertainment check out my twitter @catherine_chenn