Watching animals eat is like my biology crack. I don’t need it, I don’t have to do it, I don’t even always like it, but there’s just something about critters noshing on one another that renders me wonderstruck. And nothing does it for me like the comb jelly Beroe:

So let’s start with the obvious here: in a SINGLE bite, those Beroes ate something up to twice their size. One. Bite. People. The jellies being eaten–they’re called Mnemiopsis, and they’re peaceful plankton eaters. Beroes, by contrast, are like the big bad wolfs of the sea, except no real wolf could swallow its prey whole. So how, exactly, are Beroes pulling off this gastronomic feat? Basically, Beroes are swimming stomachs with mouths attached, and while it’s true this helps them swallow big food, the real secret to their bite lies in a jelly rarity. Let us diagram:

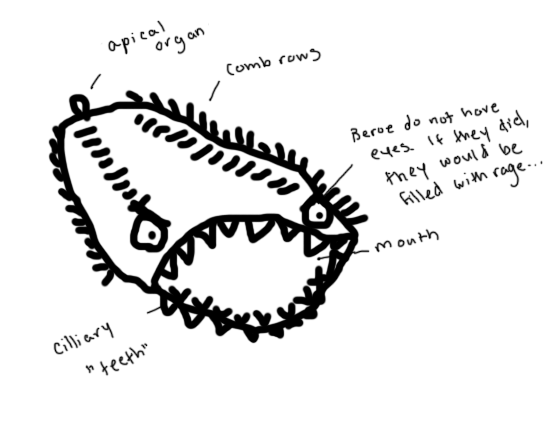

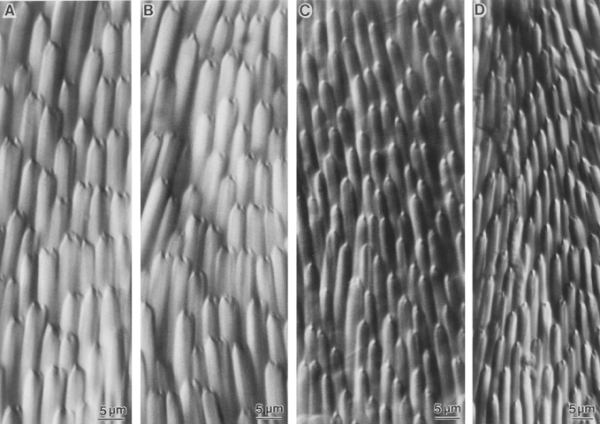

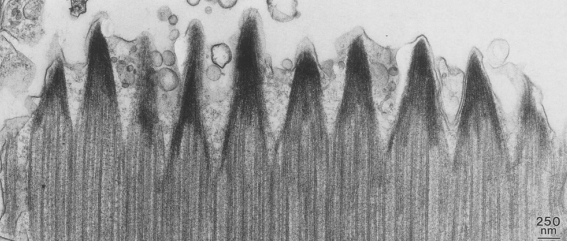

Forget the sock-shaped body, the little paddles or rainbow colors, what truly sets Beroes apart are their TEETH [1]. And they’re some of the most amazing-and terrifying-teeth I’ve ever seen:

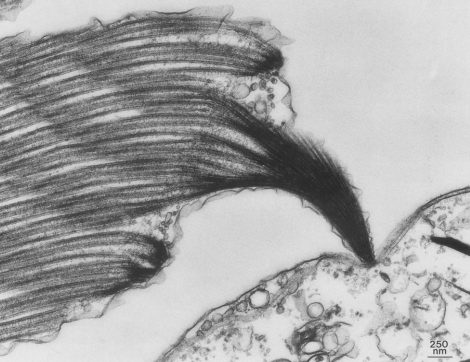

Now, they’re tiny, a fraction of a millimeter, and tiny isn’t usually synonymous with ‘terrifying’, but hear me out. Because these teeth can do something no other tooth can. These teeth can move:

Beroe teeth are made of bundles of cellular hairs. Because they’re not made of hard enamel like our teeth, each tooth is incredibly flexible, capable of changing shape; it can transform from a straight piercing-sharp dagger into a hook-like needle that digs in and holds onto prey (like the tooth pictured above). These teeth can also pivot at the base, pulling a victim deep into the stomach. Pierce, hook, pull. And there isn’t just one row of teeth, there are HUNDREDS.

In some Beroe species these fields of teeth stretch down half their stomach, half their stomach is lined with flexible, shape-shifting spines.

But is there a chance for the peaceful Mnemiopsis to escape? None. Once a Beroe has swallowed its prey, it zippers its mouth shut. Yep, that’s right–specialized cells on the edge of its lips form a zipper-like seal, making it impossible for the captured jelly to break free, no matter how hard it tries [2]. Even the researcher who discovered this couldn’t pry open the Beroe mouth, sooner ripping the animal’s body than unsticking the lips. And once the prey is zipped inside? Those same rows of teeth that pulled it in may also serve as tiny meat grinders, pulsing back and forth, slowly tearing it to shreds. After digesting, a Beroe unzips its mouth, spits out any inedible bits, and begins hunting for its next unlucky meal.

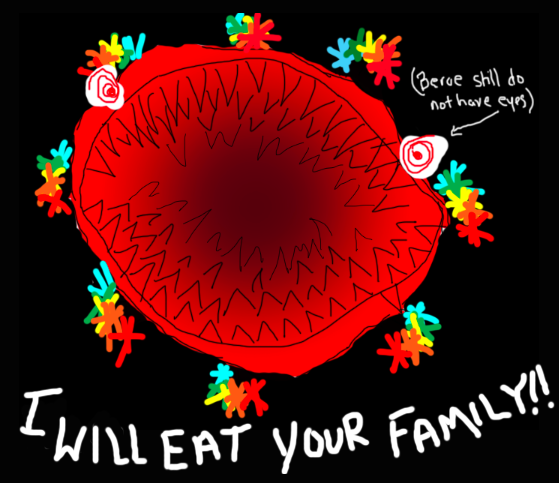

So while we may look at a Beroe and see this:

Jellies see this:

Moral of the story: They may be soft and covered in rainbows, but never, ever trust a Beroe. At least, not if you’re a jelly.

Work cited

[1] Diversity of macrociliary size, tooth patterns, and distribution in Beroe (Ctenophora)

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF00403086?LI=true

[2] Dynamic control of cell-cell adhesion and membrane-associated actin during food-induced mouth opening in Beroë

http://jcs.biologists.org/content/106/1/355.full.pdf

Additional recommended reading:

Cilia and the life of ctenophores

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ivb.12042/abstract

This is the best thing I’ve read all week. It has everything: gorgeous video, an Alexander Semenov photograph, electron microscopy, animal behavior, cartoons and excellent writing. Plus Ctenophores. Thank you.

You’re most welcome! And thank YOU! :-D

great piece Rebecca and tribute to sebastan beroe alias sid tam