Researchers have announced that, thanks to a whole slew of amazing science gadgets, they can now control the jellyfish life cycle, causing mini-jellyfish blooms in the lab anytime they want. This finding is cool enough, but how they did it may be one of the craziest science stories I’ve ever heard. We’re talking Frankeinstein’s jellyfish over here. They used pretty much every awesome science trick in the book (including two rarely combined words: jellyfish and electricity). But before we talk Franken-Jelly and electric shock, let me show you why jellyfish are so damn strange in the first place, and why their life cycle is so difficult to crack.

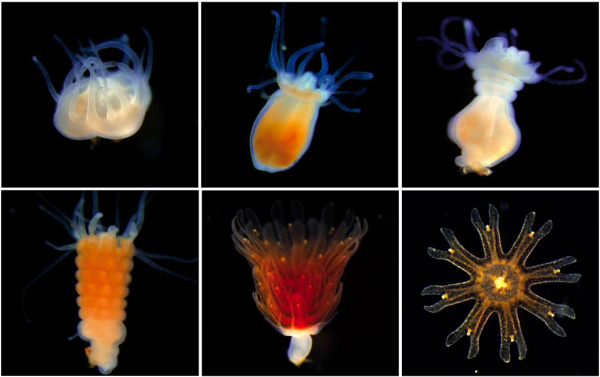

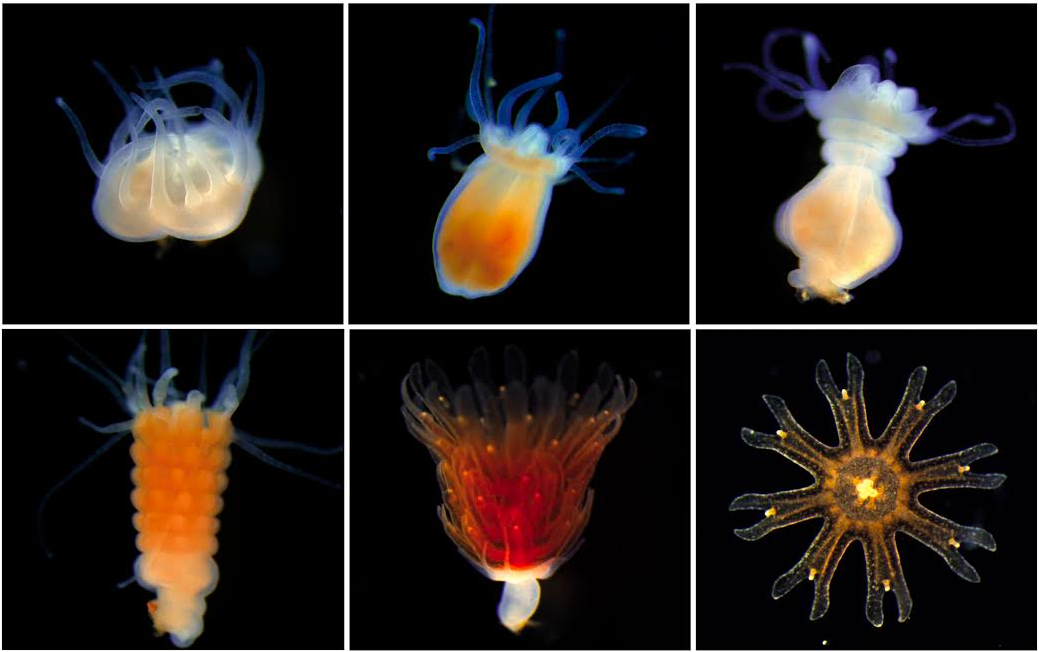

Jellyfish, most of the time, look nothing like jellyfish. They look like tiny little bread-crumb sized sea anemones.

These “polyps”, as they’re technically (tragically?) called, can hide all over the place; under shells, docks, logs, etc. They’re also really good at copying themselves. One polyp can turn into hundreds over a season by growing and dividing. The best part? Like little living 3D printers, they can churn out copies of their same old polyp body over and over again or they can mix things up and start making a different body: Jellyfish. Jellyfish as we know them start their lives as little jelly rolls (see what I just did there?) on the polyp body.

Each jelly roll develops into a wee jellyfish, which eventually breaks off and swims into the ocean, starting the whole cycle over.

Ever wonder why jellyfish appear only at certain times of the year? One reason is that while being exposed to cold water (like during winter) polyps started churning out jellies. So there is something about cold weather that flips the switch from polyp mode, to jelly mode.

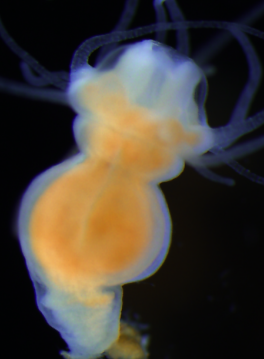

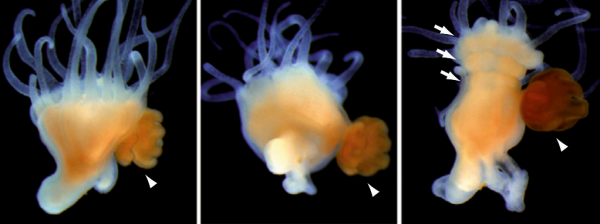

Now, let’s talk Frankenjelly. Scientists wondered if there was a molecule that kicked jelly rolling into gear. Presumably, this molecule is already present in jelly rolls, but not in warm, cozy polyps. Thanks to the polyp’s handy hobby of cloning itself, scientists had a genetically identical collection of polyps to work with. Translation: they could stick pieces of one polyp onto another without any rejection. So, what would happen if, say, you stuck a piece of jelly roll onto a naive polyp? Answer: the host polyp starts making jellies of its own, even though it was never exposed to cold water.

When they stuck polyps onto other polyps, in comparison, nothing happened. Meaning there is something in the jelly roll tissue that can turn on jelly making in polyps. But what is it?

Thanks to gene sequencing, scientists discovered an important clue, a gene called CL390. CL390 codes for a particular protein (a kind of cellular part) that is only present in jelly rolls, appearing for the first time when polyps are placed in cold water. The scientists predicted that, like an inmate stuck in prison, a polyp uses this protein to tick off each day that it’s stuck in cold water. Each “tick” is the production of more CL390 protein. If enough days pass, enough CL390 builds up in the polyp to tip the scale–it freaks out, breaks out, starts forming baby jellyfish. And how do you test this idea? Jellyfish, meet electroshock.

When polyps are zapped with electricity, their cells briefly break open. Not so much to kill the animal, but just enough to let things in and out. Like briefly knocking down the cell’s tightly-held defenses. Place a polyp in a tube with some molecules that prevent CL390 from doing its job (anti-CL390), stick the tube into a tiny electric chamber, zap the crud out of it, and BAM! Now the anti-CL390 molecules that were *outside* the polyp’s cells have been granted uninvited access *in*. And what happens when you introduce anti-CL390 into the polyp cells? Suddenly a polyp about to make jellyfish slows waaay doooowwwwn. If CL390 is like the ticks of a prisoner counting the days in cold water, anti-CL390 sneaks in and erases 60% of those marks. And thus the polyp takes much longer to make jellies.

To celebrate their success, the scientists next went out and bought a bunch of drugs. Then, like any reasonable person with a boatload of drugs, they gave them to polyps. Specifically, they soaked polyps in various drugs that had a similar predicted shape as the mystery CL390 protein. Sure enough, molecules with a special kind of ring structure were able to act like synthetic CL390, kicking polyps into jelly-making mode, cold weather or not. And now scientists have a trick to trip polyps into making jellies any time, anywhere.

Some speculate that this finding may one day give humans the power to control wild jellyfish populations, but I don’t much care for this idea. Humans are clearly in the jelly’s back yard. If we don’t like them, it seems only fair that we modify our behavior, not the other way around. Instead, I love this study for the wonder. That these simple-looking, hypnotic animals have secret, surprisingly complicated lives. And with the right awesome science tools, we can begin to discover their world.

Like this article? Check out the paper here. Want to play with jellyfish genetic data? Check out their database at compagen.org/aurelia

Share the post "Scientists use electricity, drugs, to uncover the secret world of jellyfish"

This would have literally saved me a year of work during my PhD! I spent so much time getting in temperature right then waiting for them to produce enough ephyrae (baby jellyfish) to work with. This will make it so much easier for people to do lab work (which is desperately needed) on early life history stages of jellies.

For supposedly simple creatures, they’re pretty complicated.

Couldn’t agree more! I’m so happy this paper is out. It really opens up the field!

And then Dr Shubert creates a gargantuan man o’ War.