This was originally posted at alistairdove.com June 21, 2010. To see another bizarre parasitic relationship, check out Rebecca Helm’s recent piece on the marvelous world of Sacculina barnacles parasitic in crabs.

My good colleagues Janine Caira and Georga Benz wrote a paper way back in 1997 about one of the strangest parasites ever recorded in an animal. This paper has stuck with me ever since, I think because I saw the original photos when I visited George’s lab back when he was with Tennessee Aquarium (he’s now at Middle Tennessee State U.). So, I thought I’d revive it for you guys; the story goes like this:

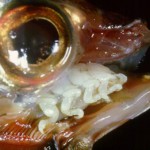

Janine and her colleagues were unable to determine the path of entry, but they showed good evidence that the eels were alive in the heart prior to the shark being killed and put in the fridge, because their guts were full of blood and there were pathologic changes to the heart. Their conclusion? That this was a facultatively parasitic relationship. In other words, the eels didn’t need to be living in the sharks heart (that would be obligate parasitism), rather they took advantage of an opportunity to get a meal. They proposed that the eels probably attacked the shark after it had been hooked and was dangling, distressed, from the longline. They had some evidence that the shark was probably resting on the bottom, which may have made it easier for the eels to find. The pugnoses somehow gained entry (hypothesised to be through the gills) and made their way to the heart, where they dined on the beasts blood up until it died. Maybe they would have burrowed out again after the animal expired, maybe they would have suffocated (remember – the eels had be swimming in and breathing the sharks blood once they were inside, how bizarre is that?). We’ll never know because the carcass went in the fridge, which ended things for the eels, but also led to this amazing discovery.

Janine and her colleagues were unable to determine the path of entry, but they showed good evidence that the eels were alive in the heart prior to the shark being killed and put in the fridge, because their guts were full of blood and there were pathologic changes to the heart. Their conclusion? That this was a facultatively parasitic relationship. In other words, the eels didn’t need to be living in the sharks heart (that would be obligate parasitism), rather they took advantage of an opportunity to get a meal. They proposed that the eels probably attacked the shark after it had been hooked and was dangling, distressed, from the longline. They had some evidence that the shark was probably resting on the bottom, which may have made it easier for the eels to find. The pugnoses somehow gained entry (hypothesised to be through the gills) and made their way to the heart, where they dined on the beasts blood up until it died. Maybe they would have burrowed out again after the animal expired, maybe they would have suffocated (remember – the eels had be swimming in and breathing the sharks blood once they were inside, how bizarre is that?). We’ll never know because the carcass went in the fridge, which ended things for the eels, but also led to this amazing discovery.

The horrifying part is that the shark was almost certainly alive as the eels made their way into its flesh and began to consume its life blood from the inside. It would have been a long, slow and nasty way to go out. It just goes to show that even when you are at the top of the food chain, you’re never really at the top of the food chain…

Caira, J., Benz, G., Borucinska, J., & Kohler, N. (1997). Pugnose eels, Simenchelys parasiticus (Synaphobranchidae) from the heart of a shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus(Lamnidae) Environmental Biology of Fishes, 49 (1), 139-144 DOI:10.1023/A:1007398609346

I read about this already some years ago but sadly never saw a photo. Wow, that´s really gross! Of course it´s not as extreme as having a living eel inside the heart, but the presence of a remora within the gill chamber is probably also not really what a molid would enjoy.

http://fishanatomy.net/webpages/fish/mola/parasites.htm

Cool! There’s something else neat on that page too. The 4 unlabeled photos that come after the remora ones show the largest monogenean flatworm in the world, Capsala martineri. Sunfish are good that way – the largest monogenean, the longest digenean and possible more species of metazoan parasites than any other fish species.

Ewww and awesome!! I had Dr. Caira for undergrad parasitology years ago. I consider her solely responsible for my now lifelong passion for parasites.

She’s a force of nature!

Oh man, this is all kinds of nasty awesome!

Thanks for the information about the tapeworm. It´s really incredible what masses of parasites are using molids as hosts.

I remember also that I read years ago about tiny “eels” found encapsulated within the abdominal tissue of groupers, I think it was in Grzimek´s Animal Life Encyclopledia about fish. I have to check if I can find the passage again. Apparantly the small eels were eaten by the groupers but tried to escape by burrying into the tissue of the digestive tract where they died and were over time encapsulated in tissue. Sadly I couldn´t find any more information about this in the net.

Besides hagfish and sea lampreys some South American catfish species of the genus Cetopsis and at least one species of aquatic ceacilian (Potomotyphlus kaupi)are also known to burry within the body cavities of freshly dead carcasses of larger animals like bigger fish or even mammals (there are really nasty videos of such catfish coming out of human corpses), and who knows if they always wait until it´s really dead, especially when it´s only close to death, injured or caught in a net.

Really amazing

Those heartless eels…

While this is weird and gross, in no way does it rise above the (aforementioned) crab barnacle.

That thing is freak-show-horror-story on acid.

…crab barnacle, vampire catfish, buccal isopods, Pearlfish…… one mans cavity is another mans niche!

Perhaps they were following the heat as the shark cooled in refrigeration, the heart may have been the warmest place after a while. What pathologic changes to the heart did they find? Did this occur over time? It doesn’t sound like it, it sounds like eels trying to escape the cold.