I’ve been temporarily released from my social media silence to talk about my latest paper, which is published in the open-access journal PeerJ. So first of all HAI EVERYONE! Second of all – here’s how I accidentally discovered that gooseneck barnacles are eating plastic, and why it’s so difficult to figure out what effect that is having on the ocean.

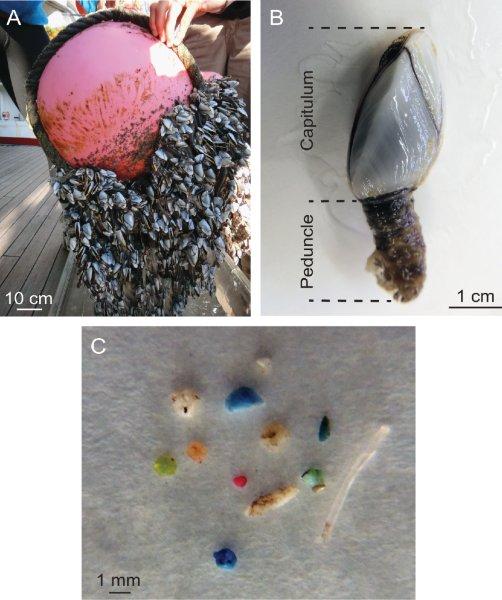

On my 2009 expedition to the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, otherwise known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” I collected a bunch of barnacles, along with samples of a lot of other organisms that were growing on the debris, because I was interested in seeing what species were there. Gooseneck barnacles look kind of freaky. Like acorn barnacles (the ones that more commonly grow on docks), they’re essentially a little shrimp living upside down in a shell and eating with their feet. Unlike acorn barnacles, gooseneck barnacles have a long, muscular stalk.

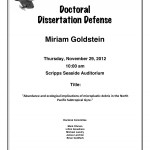

It took me a couple years to get around to processing those samples, but eventually I found myself in the lab dissecting barnacles in order to identify them. As I sat there, I thought “Well, I’m working on these barnacles anyway – wonder what they’re eating?” So I pulled out the intestine of the barnacle I was working on, cut it open, and a bright blue piece of plastic popped out. I reached into my jar o’ dead barnacles and dissected a few more, and found plastic in their guts as well.

Thinking about it logically, it makes a lot of sense that gooseneck barnacles are eating plastic. They are really hardy, able to live on nearly any floating surface from buoys to turtles, so they’re very common in the high-plastic areas of the gyre. They live right at the surface, where tiny pieces of buoyant plastic float. And they’re extremely non-picky eaters that will shove anything they can grab into their mouth.

But, since I didn’t really collect barnacles with this study in mind, I didn’t have enough samples to figure out how widespread this phenomena might be. Fortunately, I’d been lucky enough to collaborate with the wonderful Sea Education Association and one of their chief scientists, Deb Goodwin, for several years. SEA kindly took samples for us, and Deb, once a perfectly respectable remote sensing expert, got deep into some pretty smelly barnacle guts.

After dissecting 385 barnacles, Deb and I found that 33.5% – one-third – had plastic in their guts. Most barnacles had eaten just a few particles, but we found a few that were absolutely filled with plastic, to a maximum of 30 particles, which is a lot of plastic in an animal that is just a couple inches long. We also analyzed the type of plastic in the barnacle guts, and found that it was approximately representative of plastic on the ocean surface – the barnacles are probably just grabbing whatever they come across and shoving it into their mouths. Barnacles are perfectly capable of pooping out plastic – I observed plastic packaged up in fecal pellets, ready to be excreted the next time the barnacle had access to a couple minutes and a magazine – so it is very likely that more barnacles are eating plastic than we were able to measure.

So, this is disturbing. As I’ve discussed many times, there is a ton of plastic in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyres (but no island!) and it is being eaten by birds, turtles, and fish. And now we’ve documented plastic ingestion in a very common invertebrate – probably the numerous animal living attached to the plastic – as well. But just finding plastic in barnacle guts does not really tell us much about how plastic is impacting the oceanic ecosystem. This is because we don’t really understand how barnacles are interacting with the rest of the ocean.

Gooseneck barnacles aren’t necessarily incredibly central to the North Pacific Gyre ecosystem. The barnacles are voracious predators, but since plastic is so patchy, it’s not clear that they eat enough zooplankton to really affect the ecosystem – and a lot of the food I found in the barnacle guts were their own cyprid babies. (Barnacles are nasty cannibals, apparently.) They’re eaten by a few predators – a pretty little sea slug and some crabs – but fish don’t seem that interested in barnacles, maybe because those fish didn’t evolve with a ton of floating debris. If barnacles are an important prey item, it is possible that their ingestion of plastic particles could transfer plastic or pollutants through the food web, but it is far from clear this is the case.

However, the most dire effects could be the most subtle. The subtropical gyres are 40% of the entire earth’s surface, and so they are very important to controlling the way that nutrients and carbon move around in the ocean. The microbes and animals that live on plastic debris are not the same as the microbes and animals that float around in the ocean, and may not act in the same way. It’s such a cliché for a scientist to call for more research, but we just don’t understand enough about the way that the ocean works, and enough about the way that plastic affects the ocean, to really say what the effects of barnacles eating plastic might be.

Of course, none of this uncertainty changes the fact that plastic trash does not belong in the ocean, and we need to be a lot better about preventing it from getting in there in the first place. However, I am skeptical of plastic cleanup schemes, so please read these Open Ocean Cleanup Guidelines (which I co-authored) and Dr. Martini’s post before you suggest that we just clean it up. I think we are probably stuck with the plastic pollution that we have, so understanding what it is doing to the ocean is important.

I’ll be back in a couple weeks to do another behind-the-scenes post on a second debris-related paper! In the meantime, I’m happy to answer your questions about the barnacles.

Share the post "Behind the scenes: plastic-eating barnacles in the North Pacific Gyre"

Since you have the gps locations, i will ass ume you got the zooplankton counts at the same locations.

since the barneys can pelletize it, it would seem like percentage of plastic in the gut, would correlate to low througput of other food, or lack of science journals.

If they are collecting less regular food, then they would be flushing out pellets, and cleaning the gut more often.

Seems like you should be able to correlate plastic consumption, to lower zooplankton currents. Can a standard TDS meter on remote track the plankton densities ?

Thanks for the info, i have been following CDEBI and Joides, havn’t seen any sci on the gyre in a while.

PS, can you feed the barneys magnetite laced food to eat with their plastic?

Then you could just put magnets around, and they will passively clean up the micro trash….

Hello Jerome,

It is definitely possible that the plastic means that the barnacles are eating less zooplankton. But it would have to be a lot of plastic to have an effect on them, since they move food through their gut in a matter of hours. We didn’t observe that much plastic in most of the animals, though there were some notable exceptions, like the barnacle with 30 pieces in its gut.

A TDS meter cannot track zooplankton in the ocean since the ocean is absolutely FILLED with stuff. I think all a TDS meter would say is that the ocean is salty. There are techniques to count zooplankton, like the video plankton recorder, but I don’t think they’d be helpful for this particular question. Currently the best way to know how much plankton is out there is just to tow a net around, old-school. Unfortunately in this study we weren’t able to do that in the same places that we collected the barnacles, so we aren’t able to make comparisons.

I don’t think feeding the barnacles magnetite would work, since (other issues aside), the scale is vast. The North Pacific Gyre alone is 3 times the size of the continental United States!

Fascinating, and worrying. Thanks for sharing it, and for dissecting out the stomachs of 385 barnacles.

So, do you think that they have an impact since most things don’t eat them? I mean, a bird won’t eat it and then get sick because the barnacle had plastic in it, right? I just made a video about how plastic bags (and plastic) ends up in the ocean and how it breaks into smaller pieces, that is really sad that the barnacles are eating it too. I am part of the Colorado inland ocean movement and I think we need to let people know about what to do with their plastic so it doesn’t drift off into the garbage patch, but I think you are right, we are stuck with it and that’s gross.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A7dHiYKo2qk&feature=youtube_gdata

loverofwhales.wordpress.com/

Grace, your video is terrific! I love it! And I truly don’t know what the impact of barnacles eating plastic might be on the ecosystem – if the barnacles drift close into shore there are fish that would eat them, but not all that many out in the ocean. The albatross eat plastic anyway, with or without barnacles. So we have to do more science to figure out what is going on.

Also I had another question, I don’t know exactly where the garbage patch is in relation to whale migration up that way as the whales (humpbacks, grays, blues and others) head north to eat, are they passing by the patch? Is it killing off their food or are they eating some of the bits as they troll for food?

Thank you about the video.

I’m not a whale expert, but I don’t think they go through the area with the most trash. I also don’t think that whales feed when they’re migrating. But I would definitely defer to any real whale experts if anyone is reading this – whales are pretty far outside of my area of expertise. We did see sperm whales in the garbage patch area, but they were feeding on deep sea squid and were unlikely to be interacting much wih the trash.

Hi Grace,

I study whales, so I might be able to help with your question. :)

Gray whales do not spend a lot of time in the area of the garbage patch, because they generally travel pretty close to the coast (although there are some rare exceptions: http://www.learner.org/jnorth/tm/gwhale/varvara_tracking_tagged.html). Humpback whales and blue whales are also thought to do most of their eating to the north and west of the garbage patch. Sperm whales and other animals that feed in the deeper ocean probably wouldn’t encounter as much plastic (as Miriam said). However, that isn’t to say that any of these species of whales wouldn’t eat plastic at some point. Many whales have been found with bits of plastic in their stomachs (see this article: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/36664196#.Umw51BagnR0 ), and there is far too much trash and plastic in the oceans. We as humans need to make an effort to reduce the amount of trash that we make and that ends up in the oceans.

Good question!!!

Are these fecal pellets with plastic in them dense enough to sink? Do you think they could be transporting the plastic into the marine snow system?

That’s a really good question – we don’t know. The plastic particles float, but it’s possible that the fecal pellets are dense enough to still sink. That would definitely be something to look at in the future.

So, pretty fascinating and… promising? Maybe “Gaia” (tongue in cheek) will do what she has done always, which is find a way, adapt, and profit from new circumstances??

Are there bacteria helping to digest the plastics? Are you guys witnessing the first step in a major adaptive radiation?

Very, very interesting, thanks Miriam.

There are bacteria that _maybe_ digest plastic – they are certainly drilling into it. I don’t think the barnacles are able to digest plastic at all, though. Food wise for them, it’s neutral at best and harmful at worst. But the barnacles certainly profit from the plastic in another way. They need to attach to a floating object in order to grow up, and all that floating trash provides great habitat for them to live on.

Thank you, that is good news for whales! I am going to start using some pieces of trash in my art. I already use recycled things like pieces of wood that we get from the teacher supply store as canvas, but after seeing some of the trash art at the WAVES conference, I can use more.

OK, my prediction is that it is only a matter of time before some bacteria (maybe a gut bacteria of the barnacles) “invent” an enzyme capable of de-polymerize the polyethylene and start using all the C and H that it is there. Barnacles or other living things from the thermal vents may already have the weird chemistry needed.

Maybe any of you can think of a fundamental biochemical reason why plastic cannot be enzymatically degraded, but if it can, bacteria will find a way sooner or later.

Plastic is neutral at best and harmful at worst right now, for existing life forms, and it is ugly as hell for species like us with a sense of aesthetics. But remember, Oxygen was pretty harmful too, before some pretty strange new form of life evolved photosynthesis and started using it.

I know that thrash may provide support for marine species. I have seen the “artificial reefs” made of junk that in a few years get covered with all the Porifera, Coelenterata, Annelida and other things around, but what you describe suggests that there is a whole new niche there, ready for the right evolutionary step!! Just imagine a Barnacle/bacteria combination capable of digesting those polymers!

do you think that the increase of plastic uptake by barnacles could influence sea turtles in terms of uptake through feeding on barnacles and also through bioaccumliation in hatchlings. Also do you kmnow of any other documentated cases involving plastic accumliation in crustaceans. thanks :)

So far as I know (and I am not a sea turtle expert) sea turtles do not eat barnacles. So barnacles eating plastic probably has no influence on them. Unfortunately, sea turtles eat plenty of plastic directly. For example, according to this study, the likelihood of a green turtle ingesting debris nearly doubled from an approximate 30% likelihood in 1985 to nearly 50% in 2012. There is one other study I know of that documents plastic accumulation in crustaceans in the wild – it’s on Norway lobster. There are many more studies in the lab, mostly with copepods.