There have been a lot of tweets, blog words, column inches and TV time devoted in the last few days to the notion that Discovery’s Shark Week may have, ahem, jumped the shark. Good, I’m glad we’re having that conversation because it needs to be had. That said, the mockumentary Megalodon: the Monster Shark Lives was the single highest rated Shark Week special ever, like ever in 26 years. If you were an exec at Discovery, would you overlook that stellar result just because some people whined about it on Twitter? Er, I think not. I doubt we will see a reversal of the direction Shark Week is headed, because it’s a pattern echoed across the cable networks. Before HLN became the home of <insert this weeks salacious courtroom drama here>, it used to be CNN Headline News, where they played, y’know, headline news, in a helpful repeating loop. Before Honey Boo Boo moved in, TLC was The freakin’ LEARNING Channel. The only thing I’ve learned TLC lately is how to find the off switch. And as for H2, don’t get me started on Ancient Aliens and Countdown to Apocalypse… Perhaps the cable networks ought to just stop abbreviating these channel names, because in doing so they seem to forget, quite literally, what they stand for.

Given that things are not likely to change anytime soon, I propose we all do our bit to make Shark Week a bit more like it used to be, like we want it to be. It may have started as a Discovery marketing initiative, but like all good cultural phenomena it has long since grown beyond its origins and I think it’s fair to say Shark Week now lives in the minds and hearts of a curious and passionate public with a burning desire to know about and connect with one of the planets most incredible groups of animals. To that end, here’s 5 cool things about sharks I doubt you’ll see on TV this week.

1. They can ungrow

Wait, what? Ungrow? Like, shrink? Yes, exactly, a shark can be shorter next year than it is this year; this has been documented for several different species in wild and captive settings. How is this possible and under what possible conditions could it be helpful? Well, the answers to those two questions aren’t known for sure but we can wax hypothetical about how and why. The key to the how lies in the cartilage skeleton that is common to all sharks and rays. Much moreso than bone, cartilage is a dynamic tissue. Cells called chondroblasts and chondroclasts are scattered throughout the cartilage and they make and destroy it in a process of continuous regeneration and remodeling. This is much harder to do in bone, which does have analogous cells (osteoblasts and osteoclasts) but they have to deal with a rigid crystalline calcium phosphate matrix, which is harder to remodel than soft squidgy cartilage. Combined with some atrophy of muscle and organ cells, you can see how it might be possible for sharks to become smaller if conditions demanded it, such as food shortage or environmental changes. Very handy indeed.

2. The teeth of a great white are probably the most boring shark teeth there are

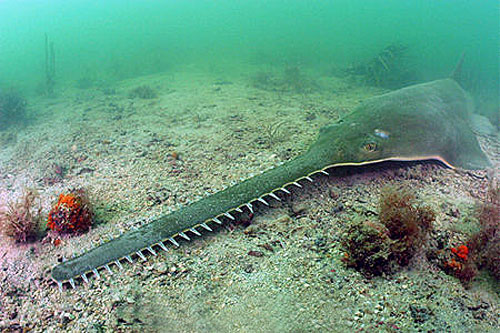

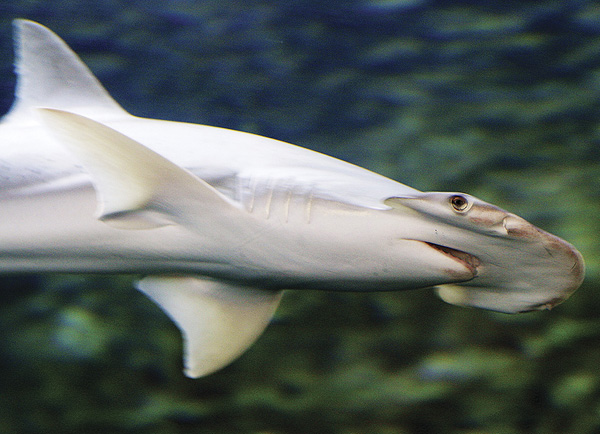

Before you do a Lumberg on me, check out these bad motor scooters:

Among the 400 or so species of sharks that currently swim the ocean, there exists a bewildering array of such tooth structures. In fact, it’s probably been one of their keys to success, because it has allowed them to feed on a huge diversity of prey items, everything from microscopic plankton to the toughest bottom dwelling invertebrates, all the way to the fatty and juicy mammals that take up a disproportionate amount of the Shark Week air time.

3. Their teeth are the least interesting part of their gastrointestinal system anyway.

There are three species of filter feeding sharks, the whale shark, basking shark and megamouth. The first two of these are also the biggest and second biggest of all sharks, by a LOT. Whale sharks get as big as Cacharocles megalodon ever did. Chew on that for a bit (well, gum it really; they have tiny, ineffectual teeth). The fact that, among a class of predatory fishes, filter feeding habits arose not once but THREE times during evolution, with different mechanisms each time, blows my mind regularly.

The filter pads of whale sharks deserve special attention in this regard because they are really something else. Derived from the leading edges of the gill rakers inside the mouth, they have become so highly branched and interwoven that the gills cannot be separated to allow bulk water to flow out through them (this is not the case for basking sharks, megamouths, or manta rays for that matter). The average pore size in the whale shark filter pad is 1.9mm, and yet they can filter out food items that are much smaller through a near-magical process called cross flow filtration. It’s one of the true marvels of evolution.

The gut of many sharks is a completely unique design called a spiral valve intestine. It’s basically a spiral waterslide for your lunch. Winding but regular, long yet compact, it’s a terrific design that natural selection has hit upon, and not found in any other group except in some holocephalan fishes, which are closely related to sharks. If you ever did find yourself in a stomach of a shark, at least you know your last act on this earth would be a wicked fun trip down a spiral slide to bum town. Wheeeee!

4. Males? Who needs ’em?

Bonnet head sharks, a smaller cousin of the hammerheads have been proven to reproduce at times by parthenogenesis, that is, without sex between males and females. In these cases, all of which have taken place in public aquariums, all female groups added to the collection as pups have grown up and spontaneously produced pups of their own, without ever having been kept with a male. Through a clever process of restoring the full complement of chromosomes after producing eggs (which normally have half), females are able to produce offspring under certain conditions without the need for a male to donate the half of genetic material usually supplied by sperm. Why they do this is not clear, but it may be an adaptation for tough times when males are scarce or populations are small, the former being likely with the latter too.

5. Zebra sharks aren’t, really.

Zebras that is. Not when they’re adults anyway. Fully grown Stegostoma fasciatum are a creamy colour with brown spots. In that regard, their scientific name (Stegostoma = covered mouth, fasciatum = striped) isn’t particularly accurate.

But when you see the babies, it makes a whole lot more sense:

What an utterly gorgeous animal! Completely harmless, like 99% of shark species (really), aesthetically pleasing and with a curious and fascinating secret of changing from stripes to spots as they grow. The class of fishes we call “sharks” are full of such amazing gems, if only the makers of pseudo-nature TV would stop obsessing over the 4 species that, on vanishingly rare occasions, have hurt people, maybe we could teach people about the rest of these spectacular natural treasures before they all disappear because we were too busy watching the wrong ones.

Re: Mini Zebra Shark…I literally said that caption. Then I read it…. o_0 I WANTS IT.

About Zebra Shark, an aquarium (Oceanopolis, Brest – France) just had baby Zebra shark from the couple already present in the aquarium. They filmed the release from the egg: http://www.oceanopolis.com/Actualites/Evenements/Naissance-de-requins-zebres-a-Oceanopolis-Brest-des-images-exceptionnelles-filmees-par-l-equipe-d-Oceanopolis

It’s in French… I didn’t find anything in English

“That said, the mockumentary Megalodon: the Monster Shark Lives was the single highest rated Shark Week special ever, like ever in 26 years. If you were an exec at Discovery, would you overlook that stellar result just because some people whined about it on Twitter? ”

No, I would establish a new channel: Mythical Animal Planet

I’d like to submit that we stop inadvertently complimenting the Discovery channel garbage with the misnomer, “mockumentary.” Per Wikipedia (sorry, fastest thing out there) a mockumentary is defined as “a type of film or television show in which fictional events are presented in documentary style to create a parody.” I didn’t watch the show, but from what I gather was no attempt at parody – just scientific subterfuge for entertainment and profit.

This drivel should NOT be confused with actual brilliant and hilarious mockumentaries like “Best in Show”! :)

Thanks for your wonderful coverage this week, DSN. Really enjoying it!

Very cool — did not know about the ungrowing.

One minor correction: it was recently discovered that Helicoprion is a stem-ratfish, not a shark. Close, though — ratfishes are still a type of cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes).

Question: aren’t the three types of filter-feeding shark possibly related? I seem to recall in particular that megamouths and basking sharks may be related, in which case perhaps it’s not an example of convergence?

Fantastic post! I will save this one for reference; I did not know any of those top 5 facts and I’m supposed to be a vertebrate biologist! For shame.

Very good.

However, I DOUBT the whale shark grows as large as C. megalodon ever did. The largest verified whale shark was 12.65 m and 21 tons. There are unconfirmed reports of 17 m, >35 tons.

But C. megalodon is typically understood to have exceeded 17 m and body masses of 50 tons +.

It is widely considered as the largest shark that ever lived.

You’re comparing a verified length of an extant animal with an extrapolated length of an extinct species based on teeth and other fossil measurements. I don’t think that is a testable argument. Its beside the point anyway, which was that there exists today and animal on par with the extinct species Discovery presented and certainly far bigger than any other extant shark, but because it’s harmless it gets no love.

I didn’t know that about Helicoprion. Cool! Megamouths and Basking sharks are each the sole members of their own family, but they are both in Order Lamniformes along with threshers, white sharks and their relatives. It’s possible that families Megachasmidae (megamouth) and Cetorhinidae (basking shark) share a common ancestor, so I shouldn’t have assumed three separate evolutions of filter feeding. You’re right, it could be two. A closer look at the feeding apparatus of megamouth and basking sharks might tell us whether they use the same mechanism, which would support a common ancestor, or different, which would support 3 independent evolutions.

Hi Sandrine, We’ve had many successful hatchings of zebra sharks from the adults we have in the Ocean Voyager exhibit at Georgia Aquarium, too. We’ve also had a lot of wobbegong pups, which may be even more cute! Its great when we can rear animals in the aquarium and not need to capture them from the wild. Cheers! Al

Extrapolated or not, we have today a good idea of the approx. max size in Otodus (Carcharocles) megalodon, and modern accepted figures. Pimiento et al.(2010) ranks it as the largest shark that ever lived. The whale shark certainly approaches and enters the size range of O. megalodon but not equals with certainty the latest accepted estimates of this species (18-19 m, 50-60 metric tonnes). It is not impossible but not factual at all.

Still giggling over “a wicked fun trip down a spiral slide to bum town”.