Readers of DSN may think they know my favorite organism. Did you guess the giant isopod or did you guess the giant squid? Those beasties are truly fantastic. Large and dwelling in the deep oceans, they both check two of my boxes for awesomeness. Yet, I’m drawn to another animal. A handful of species that is neither particularly large nor particularly deep in their affinity for habitat.

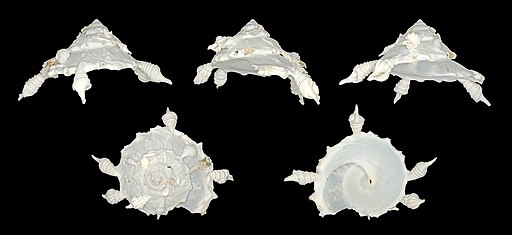

The carrier shells of the family Xenophoridae are the most remarkable bunch of snails. Both their common name and their Latin name give away their uniqueness. Xenophoridae in Latin actually translates to foreign carrying. A carrier shell will cement stones, other shells, sponges, and other debris to its shell. The individual pieces of foreign matter become larger as the snail grows and is often cemented to outer shell at regular intervals.

Why would an animal glue other things to itself, including other snails? Shell spines serve as a wonderful defense for snails. Obviously spines are pokey but they also increase the effective size of shell. Pain and size make it hard of predators to manipulate the shell into their mouths and down their gullets. Indeed, the objects also afford some camouflage. Most interesting, is that Xenophorids stay between the shell and ocean floor to feed. That cage of spines, or “spines” as the case may be, protects them. Nothing can get in there to munch on their little heads.

But, making spines is costly. It takes o’ so much energy and really who can be bothered? Shell material is soooo expensive. So instead of running down to the Home Depot to buy your own lumber why not steal your neighbor’s instead? Or in this case steal your neighbor and use his body as a ceiling support.

Three groups of Xenophorids exist. Onustus with four species and Stellaria with five species glue small things to themselves but most of the shell remains exposed (>70%). In contrast the Xenophora with about 20 species is ostentatious in how much bio-bling they will put on themselves. They are the Mr. T of gastropods. You can see some great examples at ebay. Though I would encourage you not to purchase any of them as they are often collected live.

How exactly do Xenophorids glue these foreign bodies to themselves? Snails possess a mantle, thin layer of tissue that covers the body and contacts the internal shell. This is the part of the sail that secretes calcium carbonate in a protein matrix to grow new shell. A Xenophorid will grab an object with their muscular foot and hold it place on the shell while the mantle secretes a little mollusk glue, that calcium carbonate cocktail, to fix it.

But this is just the start! Xenophorids do not dissuade neighbors from joining the party on their own volition. Shells can have sponges, corals, hydroids, polychaetes, brachiopods, and sea squirts. I’ve personally seen specimens that have sponges 5 times larger than the actual carrier shell.

But this is just the start! Xenophorids do not dissuade neighbors from joining the party on their own volition. Shells can have sponges, corals, hydroids, polychaetes, brachiopods, and sea squirts. I’ve personally seen specimens that have sponges 5 times larger than the actual carrier shell.

Given that Xenophorids date back to the Jurassic, they are the true originators of bling.

This is utterly absurd! I love it when things are weird in a weird way!

That’s incredible… just… wow 8O

Fantastic!

!!!!!! Nature is awesome!