O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?

– “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”, Wallace Stevens

————-

I would like to move beyond mythbusting.

I give a lot of public talks about my research on plastic trash in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, and after every talk, someone comes up to me and says “Wow! I really thought there was an island!” (Well, in one memorable instance, a woman came up to me and said, “YOU MEAN IT WAS ALL LIES???”) I smile and say, yes, it’s a common misconception, and no, I really don’t know where it came from originally, but it probably has to do with the art chosen to illustrate news stories about open ocean plastic pollution, like my nemesis Canoe Guy.

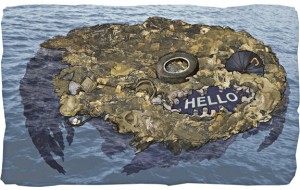

So when I heard there was not one, but two upcoming graphic novels about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and that both depicted the patch as a giant floating island, I confess that I was a bit overcome with despair. I’ve spent so much time and communication energy trying to combat the misconception of the floating trash island. Why did these artists choose to portray it like that? So I asked them.

I’m Not a Plastic Bag, by Rachel Hope Allison, wordlessly tells the story of a lonely garbage-island-creature through lush art. It’s a gorgeous book. I was struck by how poignantly the illustrations communicated the beauty and desolation of the open sea – the endless horizons, the changing clouds, the single squid outlined against infinite blue. And the poor garbage island! I felt so bad for it!

Allison became interested in the garbage patch when an oceanographer ex-boyfriend sent her an article. In a phone interview a few weeks ago, she told me she was shocked that something this large could exist “in this modern age where you assume that everything is tracked and we’re aware of it.” She wanted to tell the story of the Garbage Patch, but without being “preachy and didactic,” so she decided tell the story from the perspective of the garbage island itself – “the perspective of something that has inherited a problem that it hasn’t created, but still has to live with it.”

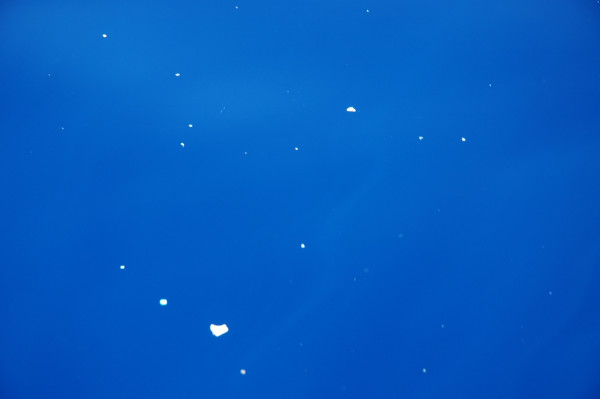

I’m Not a Plastic Bag is specifically focused around environmental activism, with an educational supplement in the back, done in collaboration with Nick Mallos at the Ocean Conservancy, that explains that “the Garbage Patch does not appear as a giant floating landfill…but rather a trash stew…While there are areas of dense debris, much more common are seemingly barren swatches of ocean full of broken down debris…” The supplement is filled with photos of beach cleanups and entangled wildlife, but there are no photos of what the North Pacific Gyre actually looks like – which is to say, like regular ocean with tiny, nearly impossible-to-see bit of plastic.

When I asked Allison about why she chose to portray a solid trash island, she laughed and said “I have pangs of guilt sometimes – is this [the island] problematic? I hope not!” She went on to explain:

I was in the story trying to figure out a way to visually communicate & make it [the garbage patch] a character, something that [the reader] could communicate with and be inspired by science. I hope that the fact that it’s so whimsical communicates that it’s not real, just inspired by the real thing. I think it’s similar to the way we draw the sun, with triangle rays. It’s a visual trope that talks about something real. At the time when I did this story it was very much focused on emotional stuff…I hope the fact that’s it speaks to both emotional ways and scientific ways give it a more balanced view. You’re totally right that myths and conceptions can be tricky and hard to balance – whether more people know about it and know about it in the correct way, and if that matters down the road.

Environmental concerns also drew Joe Harris, the author of Great Pacific, to the garbage island. Great Pacific won’t be out until November of this year, but here’s a synopsis via io9:

Set on an environmental disaster of floating trash and plastic trapped by Pacific Ocean currents, the series follows CHAS WORTHINGTON-thrill-seeking heir to one of America’s largest oil fortunes-who throws his plush life of wealth, power and pleasure aside when he decides to settle the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch and develop his own fledgling, independent nation upon it.

Chas will have to survive in the junk and waste-strewn dead zone, battling the elements, deadly marine life and animals mutated by the pollution, along with other threats which might challenge him for resources, including hostile island natives and even the United States Navy. He will build his new country, forge treaties with other ones and fund development and transformation of his own plastic island which recent estimates put at about twice the size of his home state of Texas.

Harris was kind enough to sit down with me in July at San Diego Comic-Con (even though he saw my cranky muttering about the “garbage island” on Twitter) and talk to me about Great Pacific. While I promised him I wouldn’t give away any of the plot points, I can tell you that it looks super fun – who doesn’t like a giant octopus? Check out this preview video for a sense of the art.

I asked Harris to explain why he chose to set his comic on the mythical trash island. “I find it to be fascinatingly horrific on a large scale, and I’m floored by how many people have not heard of it,” Harris said. “I just found it fascinating that this has been going on for decades, getting worse and worse.” Harris saw his science fiction series as a “license to be fantastic…and to shine perhaps a hotter spotlight on this than might be warranted. When I get to the underpinnings of this, I’m no less awed in the most disgusting way.”

Harris hopes that people would be just as horrified by the reality of the Garbage Patch as they are by the filthy plastic island portrayed in his series. He sees the garbage island in his comic series as equivalent to the mutating radiation of comic books of years past – a way to express fear about the way the world is headed. “It would seem to me that enough people aren’t paying attention to issues like this, so if we could make them pay attention to the term ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch,’ I would hope there would be value in that that would bleed over into reality.”

If the upside to creating a garbage island is increased public awareness, what’s the downside? Potentially, it’s the creation of persistant misconceptions. For example, a recent study described in Discover’s 80 Beats blog (via Ed Yong) found that people are more likely to believe a statement is true when it is accompanied by a picture. So in this case, seeing the pictures of the island of garbage make people more likely to believe it is real, because it feels true. To make matters more complicated, another study found that correcting people’s misconceptions with factual information actually does very little to reduce their belief in “false or unsupported claims.” Once these misconceptions take root in people’s minds, they’re almost impossible to counter, no matter how much data to the contrary is out there, or how many lectures people hear from a dorky scientist lady in an Octo-Pi tshirt.

Because of all this, I picked up Andrew Blackwell’s “travel guide to the eco-apocalypse,” Visit Sunny Chernobyl, with a certain feeling of dread. That he had titled his chapter “The Eighth Continent: Searching for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch” did not lift my spirits. Blackwell visited the patch in 2010 with the nonprofit group Project Kaisei, an organization dedicated to cleaning up the plastic. [Full disclosure: Project Kaisei partially funded the 2009 Scripps plastics cruise for which I was chief scientist.]

But then I read it, and it was wonderful. Blackwell has written the single best explanation of the harm done by garbage patch myths that I have ever seen. From the book:

[The search for a high concentration of floating trash] was the paradoxical symbiosis that can afflict any activist. You come to depend on the problem you’re fighting. That we were so focused on finding the Garbage Patch in a concrete and spectacular form was tragic—particularly because it isn’t a visually spectacular problem. As we would discover once we reached the Gyre, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch doesn’t actually look like much—unless you’re paying attention. The plastic confetti are invisible unless you scrutinize the surface of the water. And the millions of plastic bottles and laundry hampers and snarls of old fishing tackle are not clumped into a single mass. Yet the Garbage Patch is indeed a problem of vast scale and implications.

This conflict between the reality of the problem and its non-visual nature is at the root of the myth of the plastic island. We hunger for a compelling image to help us understand the issue. But depending too much on spectacular imagery can actually limit our understanding. We create islands where none exist, and then waste our time searching for them. We become Ahabs without a whale.

The mythical Garbage Island is dramatic and gloomily romantic. I get that. I love art and comics and science fiction, and I would hate to see them have to confirm to some humorless idea of factual correctness. But I remain unconvinced that reaching for people’s emotions with the siren song (a particularly apt metaphor in this case) of the trash island is worth promoting persistant misconceptions. Does portraying the North Pacific Gyre as an island of trash get to a a deeper artistic and emotional truth? Or does it just send more well-meaning people hunting for a non-existent garbage-Moby-Dick?

I’m Not a Plastic Bag, by Rachel Hope Allison. Published by Archaia Entertainment, April 2012, in partnership with JeffCorwinConnect. Link.

Great Pacific, story by Joe Harris and art by Martin Morazzo. Image Comics, upcoming November 2012. Link.

Visit Sunny Chernobyl, by Andrew Blackwell. Rodale Books, May 2012. Link.

I really like it a lot when my preconceptions or just plain dumb ignorance are turned on their head, and I discover that I have been punked. A lot of the time I find myself thinking ‘mmm, not very likely’, especially when it’s a news story and I’ve read the article or the court judgement for myself. But the North Pacific Gyre Garbage Patch–yeah, I have to admit I did have an ‘island’ model for that one.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch also features in Matt Dembicki’s graphic novel Xoc, the hardcover of which was released last month, and can be seen here in inks: http://matt-dembicki.blogspot.com/2010/02/spread-in-xoc-3.html

Excellent post. I agree with you that the misrepresentation can contribute to a harmful impression – “Oh, it’s NOT an island? It’s just a few bits floating about? Then it’s not as big a deal as I thought.” The reality of it shouldn’t be considered any less problematic because people expect something with more visual impact, but unfortunately that’s what we’re dealing with… which makes me sit on the fence a bit. I completely see where Harris is coming from, the hope that the horror of the island does bring attention to the real thing, but I fear greatly that people will continue to pass it off as a non-issue because they can’t see (or indeed conquer) it. It’s a big enough problem as it is, and doesn’t need to be embellished to appear any worse. It’s a shame that that’s what makes most people look at it at all.

I just had the thought that if the garbage patch was clumped into a single mass it might actually be easier to deal with. It’s like spilling a cup of coffee on the counter vs having your percolator explode (this has actually happened to me). In one, you know where the mess is, how big it is, and what’s gotten coffee stains. In the other, there are microscopic coffee bits everywhere that are spread throughout your entire living room. It’s a lot easier to understand the consequences of a problem that you can see all at once.

Of the more than 200 billion pounds of plastic the world produces each year, about 10 percent ends up in the ocean [source: Greenpeace]. Seventy percent of that eventually sinks, damaging life on the ocean floor [source: Greenpeace]. The rest floats; much of it ends up in gyres and the massive garbage patches that form there, with some plastic eventually washing up on a distant shore. Most is under the surface.

I think that the mythical island of garbage can do a lot of damage to our perception of where the plastic problem really is. Here in Maine there are thousands of microplastic particles in just one liter of seawater from off our research dock (there’s a lot of fishing around here). The problem isn’t just out in the North Pacific Gyre — it’s everywhere. Not realizing that it’s right at your doorstop can keep you from working on the plastic problems right in your own community.

I’m a professional in the oil refining business, so I also constantly battle myths about energy availability, gasoline prices, climate change, and the quality of our environment. My most frequent answers are:

— The planet still has abundant supplies of fossil hydrocarbons. But our biggest untapped source of energy, especially in the United States, is conservation.

— Gasoline prices are high (primarily) because we keep buying the stuff. Data published by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) show a clear correlation, going back to the 1970s, between the price of oil and consumption. An unfortunate contributor to high prices is American politics, especially the requirement to blend ethanol into gasoline. Another culprit is the 35 cents-per-gallon ethanol subsidy paid to oil companies (such as the one for which I work). In practice, these require us to pay farmers to use immense amounts of diesel fuel and fertilizer to grow corn, from which the energy yield is, even by optimistic estimates, <1.15 time the energy cost. Ethanol-from-corn raises food costs, threatens water tables, and promotes eutrophication in lakes and streams.

— There is still a lot of legitimate debate about the impact of anthropogenic CO2 on climate change. But there is no question that we are pumping enormous amounts of CO2 into the air. There is also no question that the best way to reduce CO2 is to promote energy conservation. With conservation, everybody wins.

— Like the North Pacific garbage island, the impact of the oil industry on the environment is misunderstood. In some ways it's worse than it seems; the Deepwater Horizon spill disappeared from the surface, but its impact still lingers. In other ways, it's not as bad. The impact of the oil well fires in Kuwait was not nearly as dire as predicted.

I could go on forever about this. My thoughts appear in some well-documented, highly technical, poorly written book chapters. If you want to know where to find them, please let me know.

Thank you for the clarification on this. I am a textile artist working on exactly this theme at the moment.

Making little bits of debris making plastic cloth, stitching into wood pallets and trying to make them look beautiful!!

I’ll have to remove ‘islands’ from my artist statement now and add ‘coagulated assemblages’ instead maybe??

Pics on my website in due course.

Thanks so much for this essay. It is frustrating when people get behind the right cause for the wrong reasons, and it leaves the cause vulnerable, because some will think that when their wrong reason is debunked, the cause itself is debunked. By being so clear about the nature of the Pacific’s garbage problem, you’ve defended the cause of taking action against the accumulating danger of plastic waste.

Thanks for the kind words, Mitch. That’s exactly why I do it!

Hi Miriam, I’ve had my webpage about the trash vortex up for a couple of years, I’ve had an image showing up here of a man on canoe paddling through a sea of very visible trash. I guess when I read about the great pacific garbage patch and found this image on the web claiming to be from there I was sucked in by the imagery.

This year a number of students and book writers got in touch to ask for permission to use this image. Not too long later a journalist (Mitch T), got in touch with me and I was subsequently informed me about the truth of it being non-photogenic.

Could I please replace that inaccurate photo with the one from this article so the word can be further spread?

Thanks, Tom.

Thanks for the comment! I tracked down canoe-man a while back – here’s the original image from Jay Directo at AFP/Getty. You are most welcome to use my photos, but please credit me & Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Thanks very much Miriam. I have updated that page now will full citation. I never had the original man in a canoe reference, so really excellent to get that, thank you!

Miriam, being that the trash vortex is non photogenic, has there been measurements to calculate the density of plastic particles in the water (not sure of the scientific terms here)?

Yes, I have done a lot of those measurements myself! There’s links to my recent paper showing an 100-fold increase in tiny plastic particles (and links to the press release & media coverage that go with it) here.

Thanks for the link, the abstract is interesting. How long does it take a plastic bottle to turn into x amount (home many?) microplastics?

I’m not aware of any solid estimates on that. I can tell you that we DON’T get PET (the plastic that bottles are made of) microplastic on the surface of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, because PET is denser than water and sinks. (unless it is still in bottle form and can float with trapped air.)

Thanks. So we need a voyage to the NPSG in a submarine to see if all the PET bottles can be found.

I can not understand your thinking on this matter, whether people think it is a physical island or not, it is the only thing bringing ANY attention to the topic at hand. All I see you doing is affirming to people there is NO problem at all, as soon as they know it is not that bad, it will be gone from their memory completely. As it will be from mine, now you have corrected my impression on it.

I think the damage you are doing on you egotistical quest, is far more than you realise.

If it wasn’t for the impression on it, no one would know about it, stop killing the cat that created the exposure.

There is actually a lot of attention on the real problems of oceanic plastic pollution – it is not necessary to invent a plastic island for the public to be concerned. See media coverage of the 5 Gyres expedition to the western Pacific, the TARA expedition to the Antarctic, SEA’s work in the North Atlantic, Mark Browne’s discovery that fleece clothing sheds microplastic fibers, and my own research on the 100-fold increase in plastic in the North Pacific, just to name some examples off the top of my head. If we want action on this issue it is important to give decision-makers the best information available – and that means making sure that people’s concern is based on the already-horrible truth, not on a false misconception. Thinking that the ends justify the means ALWAYS backfires in the end.

Yeah you tell her, Don L. Once a year, the accumulated plastic also gains sentience and unites into the shape of a giant monstrous octopus, but Ms Goldstein utterly refuses to inform the public about the Great Pacific Garbage Kraken – even though it would certainly stir us all into action – simply on the absurd grounds that it isn’t actually real. For shame!

Very interesting article. I agree that we need the truth. If nothing else, dealing with a giant island of garbage that could scoped up is very different than dealing with microscopic plastic trash. If people think it’s an actual island of easy to pick up trash, they’ll just think that we can hire a few boats to go out and start cleaning it up. How do you clean up microscopic plastic without running the risk of huge amounts of small critters being removed as well? This is one of those cases where we need to start with reducing the trash that gets there. People won’t understand that unless they understand the true nature of the problem.

Thanks, Ed. Thanks a lot. We giant octopi-made-out-of-plastic-garbage have it bad enough without you besmirching our fine reputations. Needless to say, Ms. Goldstein’s vile, slanderous lies about us have indeed come to our attention and we *will* be taking legal action against her, but it’s damn hard to *get* the proper legal paperwork out here in the middle of the Pacific, let alone fill it out. Our so-called friends the giant squid keep squirting ink on it. And laughing. And running away. Bastards.

In any event, I can clearly see you’ve taken Miriam’s side already, but I ask you: IF YOU PRICK US, DO WE NOT OOZE? HUH? DO WE, ED?

Oh, and Miriam: If you get rid of the garbage, we will no longer exist. You know who else didn’t want octopi-made out of plastic garbage to exist? HITLER.

Check us out. We are extremely interested in what you do and are doing. Great Ideas on Spreading the facts in an imaginative and creative approach. Would you mind if we mentioned you on our website?

Miriam, While I appreciate your diligence in presenting accurate information on the nature of the gyre, let’s not minimize the scale of this catastrophe that has befallen our oceans. It’s not a monolithic island of trash floating on the surface, and maybe it would be best if it’s not pictured as such. In reality, the character of this environmental disaster is much more insidious because it cannot be easily observed. The trash within breaks down into microscopic particles, forever impacting the chemistry and marine ecosystems of our oceans, the very foundation of life on our planet. There is no way to calculate the magnitude of how this has already effected our seas since the petrochemical revolution has ramped up in the last century, a mere blip on the timeline of earths history. There is no reversing this. All of the amazing wonders of our technology cannot save us from it, even if today were to mark the last day a single plastic cup found its way into the sea. Whether it’s an island of trash or an abstract blob composed of trillions of particulates, I will continue to visualize the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in the same way I have since I first learned of its existence- as a complete disaster of free market capitalism, where the immediate needs of corporate profits and disposable culture is destroying everything that has true value.

While I may not be a scientist, I am a human being on this planet….can we not all agree this has become a catastrophe for our oceans? We must stop using plastic so much, stop driving our cars on fossil fuels, learn to conserve and maybe go back in time and use old ways that’s weren’t so harmful to our environment….seem s we just do everything out of profit….shouldn’t our greatest profit be the well being and health of our planet and our regard for our future generations…living in Alaska I have seen the wildlife and ocean change, we as a world must strive to live with the world, and not abuse the world…..James Dean lasiter…musician and earthling…

wow,it’s great reading all the comments.. believe it or not, but i never knew there was a garbage island..therefore my concern is that this is becoming a bigger problem every day, why? because theres not an awareness about this problem, I might be one out of five in my whole school that knows about this.

if we can start by baby steps to just get more and more people aware of this ocean pollution crisis then more people will try to make a difference. Im not studying ocean pollution or something in that direction but maybe one day i will.

If we can start re-using and recycling our plastics it will already make a difference( internationally).we recycle at home and we want to start in our schools too, but we cant save the ocean without working together.

if you read this comment and you think, ” nah, its not my problem, it has bad effects on animals but im still okay” then i want to tell you.. yes you are okay, but in a few years time when the ocean gets so contaminated and poisened by plastic then we will be the cause of our own health problems..

i know this is lots to read and i can go on and on… so to summarise everything: RE-THINK this post, RE-USE your plastic and help to RE-ESTABLISH our oceans!