![]() Sometimes I think that those of us studying ‘minor phyla’ do so in order to prevent from developing some secret (potentially peverse) obsessions. Example: I recently attended the Society of Nematology’s 50th Anniversary meeting, where the plenary topic was….traumatic insemination. This was the subsequent topic of conversation for the next four days.

Sometimes I think that those of us studying ‘minor phyla’ do so in order to prevent from developing some secret (potentially peverse) obsessions. Example: I recently attended the Society of Nematology’s 50th Anniversary meeting, where the plenary topic was….traumatic insemination. This was the subsequent topic of conversation for the next four days.

“Write a blog post about it!”

“Have you tweeted about it yet?”

“Hey, remember that plenary talk about traumatic insemination?”

Trouble is, I wasn’t actually at the plenary. I was slated to arrive fashionably late to the conference (is there any other way to arrive, dahhling?). After hearing about something so incessantly, for so long, you begin to get a little curious. Come to think of it, that’s how my Justin Bieber obsession started.

Nematologists love to talk about nematode sex. Copulatory plugs, genital spicules, pronged gubernaculum. Traumatic insemination isn’t the only reproductive method practiced by nematodes, but it sure is a memorable strategy.

Io9 had some hilarious insight earlier this year:

Traumatic insemination is pretty much the most horrific thing imaginable. It really is better to be a human than an insect. We don’t have to deal with anything as horrible-sounding as “traumatic insemination.” I realize there’s no such thing as “bad evolution”…but this is some bad evolution right here.

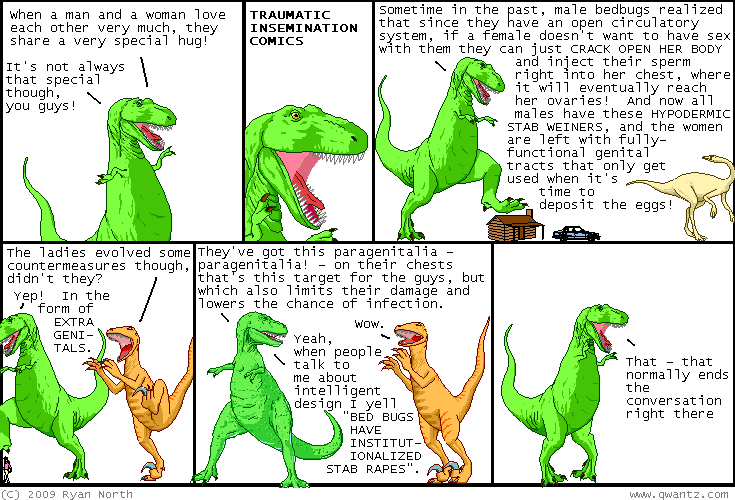

A google image search of “Traumatic Insemination” turns up bed bug photos, a Dolce & Gabbana advertisement (I agree that some of their designs are rather traumatic), and this insanely hilarious comic:

So, in a nutshell: Male wriggles up to female, stabs her body tissue with a hypodermic needle full of sperm. The victimized female then has the ridiculous ability to move this sperm towards the reproductive organs and use it to fertilize eggs. Or, if a couple of males do this in succession (stab fest or gang rape?), only the last male gets his sperm delivered—loser sperm gets shunted to the intestines and digested.

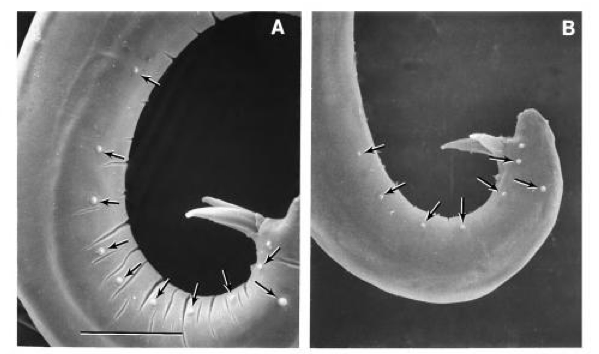

If you’re not disturbed by now, just wait. It gets worse. Coomans et al. (1988) describes this process in great detail for the nematode species Oncholaimus oxyuris:

The male apparently senses the female with its hind part. When a female passes by at a short distance from the posterior body region of the male, the latter moves violently towards the female and tries to pinch or seize that part of the female’s body that is closest by. The male uses its genital setae and ventral tail papillae as a pair of tongs. Any part of the body can be seized (Coomans et al. 1988).

The males aren’t even trying to get it in the right place. Or target the correct sex.

A copulation within the vicinity of the vulva has been observed only once. On some occasions the spicules [male reproductive organs] were inserted in the anus or the body wall was punctured pre-anally…frequent copulation attempts between males were observed in cultures with a high density of males…(Coomans et al. 1988)

And then they certainly take their time with this painful-sounding process:

During one to several (usually about 10 but up to 20) minutes, the spicules are moved separately to and fro, forming a rounded or irregular pore and a funnel-shaped subcutaneous cavity. Then follows a resting period during which the spicules are immovably anchored with their tips inside the pore and both partners are almost motionless….the [male] secretion enters the female though the copulation pore, followed by the sperm that are injected into the female during 2-4 subsequent ejaculations. After this there is another resting period, lasting up to 20 minutes, before the male withdraws its spicules and the female is freed from its grip. A would plug can be recognized above and around the copulatory pore of recently inseminated females (Coomans et al. 1988).

After traumatic insemination, an ‘interstitial channel’ forms in the female’s epidermal tissue which then guides the sperm towards her reproductive ducts. Females can also whip their tail to physically assist in this process. Nematodes aren’t the only group which use this reproductive strategy – bed bugs (family Cimicidae) ONLY mate by traumatic insemination, and it additionally occurs in rotifers, flatworms, and snails (Arnqvist & Rowe 2005).

Personally, I don’t think the apparent popularity of traumatic insemination makes it any less disturbing.

References:

Arnqvist, G; Rowe, L (2005). Sexual Conflict (Monographs in Behavior and Ecology). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 87–91.

COOMANS, A., VERSCHUREN, D., & VANDERHAEGHEN, R. (1988). The demanian system, traumatic insemination and reproductive strategy in Oncholaimus oxyuris Ditlevsen (Nematoda, Oncholaimina) Zoologica Scripta, 17 (1), 15-23 DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1988.tb00083.x

Nguyen, KB (2007) Entomopathogenic nematodes: systematics, phylogeny and bacterial symbionts. Brill. Leiden, The Netherlands.

Umm… blarg?

I am somehow reminded of this little tidbit: “Adactylidium is a genus of mite known for its unusual life cycle. The pregnant female mite feeds upon a single egg of a thrips, growing five to eight female offspring and one male in her body. Soon, the offspring devour their mother from the inside out, and the single male mite mates with all the daughters. The females, now impregnated, cut holes in their mother’s body so that they can emerge to find new thrips eggs. The male emerges as well, but does not look for food or new mates, and dies after a few hours.”

Not to mention giant squid! For serious, males seem to inject “sperm ropes” under the skin of the female’s arms. Squids definitely have CLOSED circulatory systems, so how does it ever get to the eggs? WHO KNOWS!

I, too, find traumatic insemination weirdly fascinating, ever since writing a term paper about it as an undergrad.