There seem to be three themes at the forefront of the ongoing BP saga this week: Seafloor, Seafood, and Spillage.

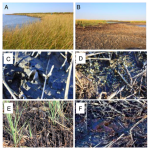

Ken Halanych (one of the PIs on our RAPID grant) is currently in the Gulf of Mexico aboard the RV Atlantis, where the submersible Alvin is zipping around doing seafloor surveys. While I sit in my office staring at Gulf data on a computer screen, the lucky bastards at NPR have been tagging along on Alvin dives that are bringing up cores that look like this:

The NPR coverage is definitely worth a listen: Part 1 and Part 2 of the series (along with lots more photos) are available on their website. The Atlantis cruise wraps-up on Tuesday Dec 14th, and until then you can find daily updates on WHOI’s “Dive and Discover” site.

The debate over Gulf seafood only seems to get more polarized every week. On one hand, you have a $30 million publicity campaign being run by the Louisiana Seafood Promotion and Marketing Board (funded with BP money, of course). As part of this push, military kitchens may be stocking Gulf seafood as a token gesture of reassurance and committment to economic recovery of the fishing industry. On the other hand, you have scientists voicing their lingering concerns, and new questions about the FDA testing gudelines–apparently Gulf Residents eat a LOT of seafood, and this may put them at a higher risk for accumulating harmful concentrations of any toxins that may be present in post-spill seafood. One news station in Florida took matters into their own hands and sent off some shrimp for independent testing (full lab report helpfully posted along with the story). The result?

Scientists found elevated levels of Anthracene, a toxic hydrocarbon and a by-product of petroleum. The Anthracene levels were double what the FDA finds to be acceptable. The scientist who tested the shrimp said she would not eat it based on the results, and the results may surprise consumers and shrimpers.

Stories like this make me worry about the relentless promotion of Gulf Seafood–is it ethical to push for economic recovery when the method (‘lets all eat lots of seafood!’) could potentially result in health issues in the long term? The BP spill was so large, and oil is obviously still present in the ecosystem. Shouldn’t we be more cautious, and thoroughly review the evidence before making reccomendations to the general public? I’ve been compiling the evidence for seafood safety for my next blogging series, “Is Gulf seafood safe to eat?”–the first installment will be posted this week, so keep a lookout!

Finally, BP is now nitpicking the government’s numbers estimating the total volume of oil spilled. Why? Because their fine for the spill will be calculated per barrel leaked. The fine per barrel is also dependent on the assignment of fault, which also explains why BP is trying to point the blame at Transocean and Halliburton: the fine per barrel would be $1100 for an accident, going up to $4300 for gross negligence that resulted in the spill. That’s a big difference in fine for millions of barrels of oil, so why not try and haggle, right? In a 10-page document, BP is saying that flow rate estimates were off and the total volume of oil spilled was 20-50% lower than the government’s estimates of 4.9 million barrels spilled. However the Times-Picayune notes that,

It’s generally accepted that the pressure at the source of the oil diminishes as it releases hydrocarbons, so the government scientists assumed the flow rate must have been decreasing all along. The scientists concluded the initial flow of oil was at least five times greater than what they had estimated in May. But videos posted on YouTube since mid-September appear to buttress BP’s contention that the output of oil increased, not decreased, over time as oil, gas and sediment tore through and eroded components of the metal stack designed to shut in the well. Independent engineers and geophysicists have told The Times-Picayune that the erosion seen in the videos would have raised the flow rate at least enough to offset the decreasing pressure in the underground oil reservoir.

i.e. Who knows what the $%#! the exact figures are.